Virtual court proceedings have become common practice in the last few years. Several years ago, the pundit Richard Susskind posed a fundamental question: Should our courts be considered a place or a service?

Certainly, pre-pandemic, our courts were thought of as places, places with high ceilings, wood-paneled walls, and a bench resembling a throne behind which our judges sat. But the pandemic forced our courts and those who appeared before them to work virtually and more remotely.

We collectively discovered that motions could be heard, testimony taken, and even trials conducted remotely using Zoom and other tools. As courts worked remotely and virtually, they became more and more a service and less a place participants had to be physically present to interact.

But post-pandemic, did this trend continue, or did our courts regress? Where do we stand today?

Routine administrative proceedings are commonplace

Certainly, post-pandemic, many courts continued to use Zoom and other tools to hear routine motions and administrative matters.

There is no question that virtual proceedings save time and costs. Virtual court proceedings eliminate the travel time of lawyers (and the ability to bill for waiting around the courthouse until a matter is called). Judges and courtroom personnel also save time, and virtual hearings reduce the time for matters to be heard, particularly now — not to mention the reduced costs of operating large courtrooms that, frankly, sit idle most of the time.

And courts seem to realize this and are adopting. For example, according to Marc Matheny, a Indiana trial lawyer, Indiana courts are using technology routinely.

He sees courts as continuing to use remote video court sessions. Adult guardianship hearings, for example, are almost all handled remotely through a court’s audio-video link. This allows the incapacitated person to appear live, without the need to bring the person from a nursing home or hospital.

It is also more convenient for healthcare professionals who can appear without having to travel. More often than not, non-evidentiary hearings and attorney conferences are handled remotely.

Matheny’s comments are echoed by Heidi Barcus, who tries cases across Tennessee and Kentucky and is the upcoming Chair of the Tennessee Bar Association. Barcus notes, “Status and scheduling conferences are now almost always remote. It sure saves a lot of running up and down the road and across the state.”

So, for many more routine and administrative matters, our courts are a service, not a place.

Virtual courts and trials have not proven popular

Most pre-pandemic trials were conducted in much the same fashion as trials have been for decades. During the pandemic, some courts began experimenting with conducting bench trials and even jury trials remotely. But success was mixed.

One of the few studies of virtual trials was conducted by the New York Commission to Reimagine the Future of Courts. The Commission studied the experience of several court systems with virtual jury trials and summarized their findings in a comprehensive report in 2021 .

The Commission surveyed courts’ practical experience with virtual trials in Texas, Florida, and California. It also reviewed the law and precedent that might be relevant to the appropriateness of remote trials.

The Commission noted, based on the experiences in three states, that while the technology exists to conduct virtual jury trials, there are a number of hurdles. Virtual jury trials can be expensive in terms of equipment and as a result are not easily scalable across a jurisdiction.

Participants are reluctant to agree to a virtual trial. Technical issues can be disruptive. and access can limit participation and result in longer trials, while problems with decorum and control of the jurors were reported.

Lawyers are not uniformly enthusiastic because, among other things, a belief that they can’t assess demeanor as well virtually as they can in person (by the way, for an excellent debunking of the myth that credibility can only be assessed by laying eyes on someone and their body language, see Malcolm Gladwell’s book Talking to Strangers).

As we will explore further, hybrid trials where some participants are in a courtroom and others participate virtually, while attractive on their face, pose practical issues.

As a result, courts are often faced with either conducting a trial entirely remotely or completely in person; most opt for the traditional in-person route.

So, post-pandemic, there is a reluctance to conduct wholesale virtual trials, and many courts have essentially gone backward.

Based on these and other studies, the results of the virtual trial have been, at best, mixed. Matheny notes that “I have not heard of any trials conducted by video since the end of the pandemic in Indiana.” Barcus agrees: “In my neck of the woods, there are absolutely no remote trials.”

Hybrid virtual court proceedings fall short

Many have speculated that trials can be conducted in a hybrid fashion, with some participants physically present in a courtroom or conference room while others are online. A hybrid approach arguably enhances convenience, but in reality, it may be the worst alternative.

Here’s the problem. Our courtrooms and most meeting rooms are designed to host in-person proceedings and meetings. That makes all in-person events simple.

Everyone shows up, takes their seats, and begins. Likewise, virtual court proceedings and meetings are pretty simple now: you call in and begin. Either way, everyone, by and large, has equal footing, and the playing field is level.

But when you go to the hybrid world, you have to make accommodations so the virtual participants, particularly for court proceedings, have the same quality access to both audio and video as those physically present — that documents can be seen by everyone simultaneously with no delay.

Otherwise, there is inherent unfairness between those physically present and those virtually present.

When the video remote component is added to the hybrid proceedings, things get much more complicated technically. For example, more cameras with greater sensitivity are needed so that whoever talks will be on screen, and more microphones are required to pick everything up.

Those present in person have to see and hear the remote participants and documents as well as if they were physically present.

Other barriers exist, control and sequestration of witnesses become more challenging, and document presentation and viewing are complicated when some are physically present, and some are not.

Preventing delays for some participants is vital to the smooth running of the proceedings. Control and mixing management becomes essential, requiring skilled technicians.

Obviously, the technical requirements and personnel to make hybrid proceedings work are pretty daunting.

But that does not mean that courts have resumed pre-pandemic business as usual. Courts have become more of a service and less of a place in several ways.

Remote judges: A viable option

One form of viable virtual court proceeding can be achieved through the use of remote judges.

A recent bench trial in North Carolina was conducted by a senior federal district court judge sitting in a Boston courtroom with everyone else in a North Carolina courtroom, for example.

West Virginia recently announced an effort to use technology to make its appellate court system more accessible by equipping five geographically diverse courthouses in the state with the requisite video and audio equipment to allow the appellate courts to hear all appeals virtually.

By doing so, litigants can participate in their appeals without being put to a significant expense and disruption.

Each courthouse has a dedicated courtroom with a bailiff and staff employee to ensure appropriate decorum. The courtrooms are equipped with a secure, professionally installed closed-circuit system, and the courthouses were selected so that no litigant will have to travel more than 90 minutes to participate in an appellate hearing.

The use of remote judges who sit in locations other than where the matter is brought opens up a lot of possibilities. A remote judge can preside over an entire trial or handle pretrial matters and motions, returning the case to a local judge for the trial — or, as in West Virginia, hear only appellate matters.

And the use of remote judges has a lot of advantages. Remote judging allows cases to be handled timely and, more efficiently and equitably, irrespective of location.

Remote judges can bring about speedier case resolutions, which is particularly important given the backlog of cases due to the pandemic.

It’s no secret that caseloads among judges are uneven. A matter in one jurisdiction can take years to resolve, while a similar matter in another jurisdiction can take months — a lengthy time to resolution is unfair.

A litigant ought not to have to be burdened with waiting years just because they happen to be in a particular location.

Moreover, remote judging can reduce the workload on local judges in overburdened jurisdictions, improving the ability of the judges to handle cases effectively.

And it’s not just the time to trial that is important to litigants, it’s the time to get to the resolution of various dispositive and evidentiary motions can be critical.

The timely resolution of these motions can timely resolve the matter — using remote judges would also allow cases to be assigned to judges with subject matter expertise.

Indeed, even jury trials could be conducted just as well, with a remote judge presiding and everyone else in a courtroom in a different location.

Since the jury is assessing the credibility of witnesses and is the ultimate. decision maker, the “inability to assess demeanor” objection is largely moot.

Using remote judges to break bottlenecks and supply needed expertise is a step toward making our courts and judiciary a service instead of a location.

Tools facilitating virtual court proceedings

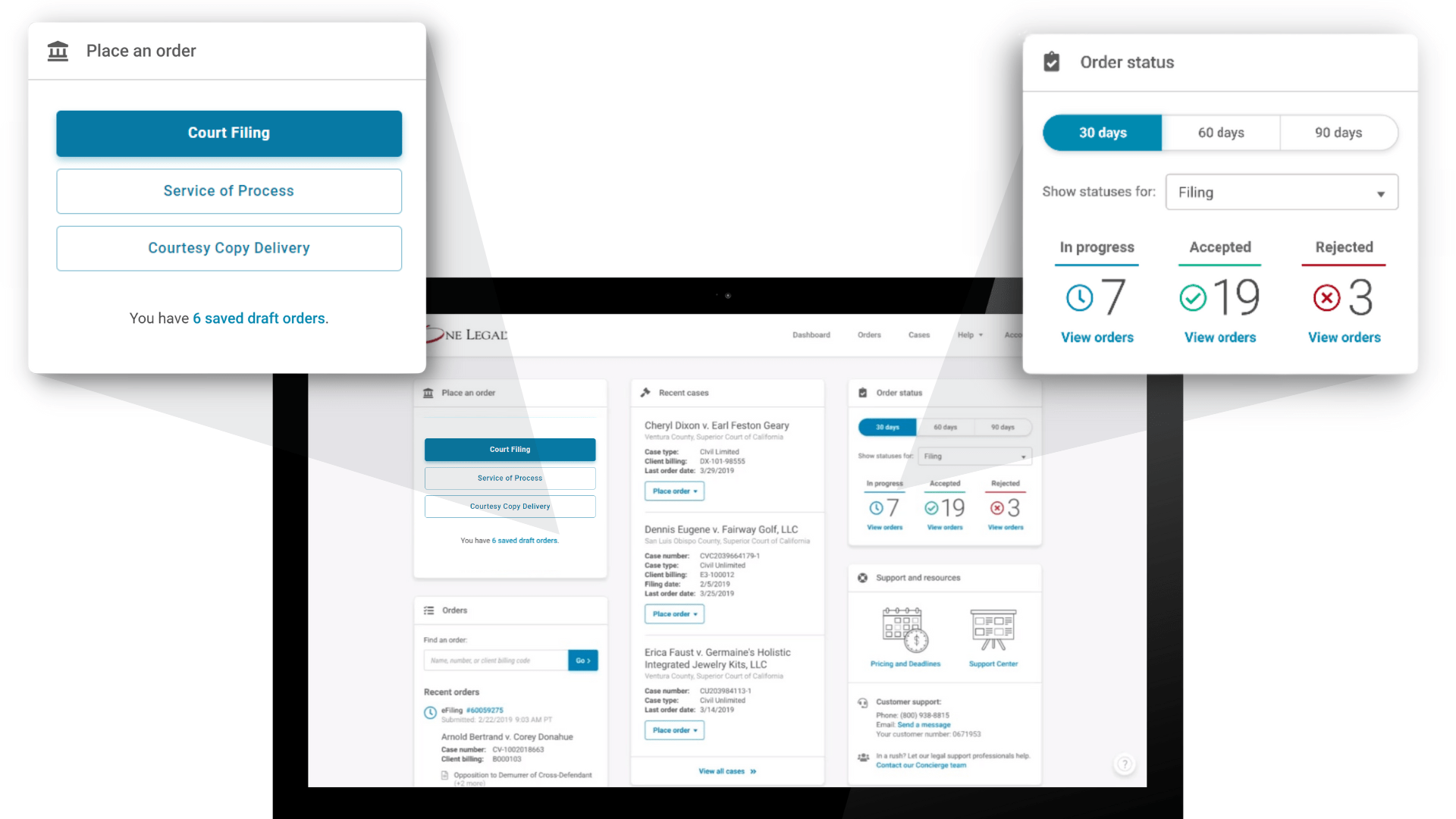

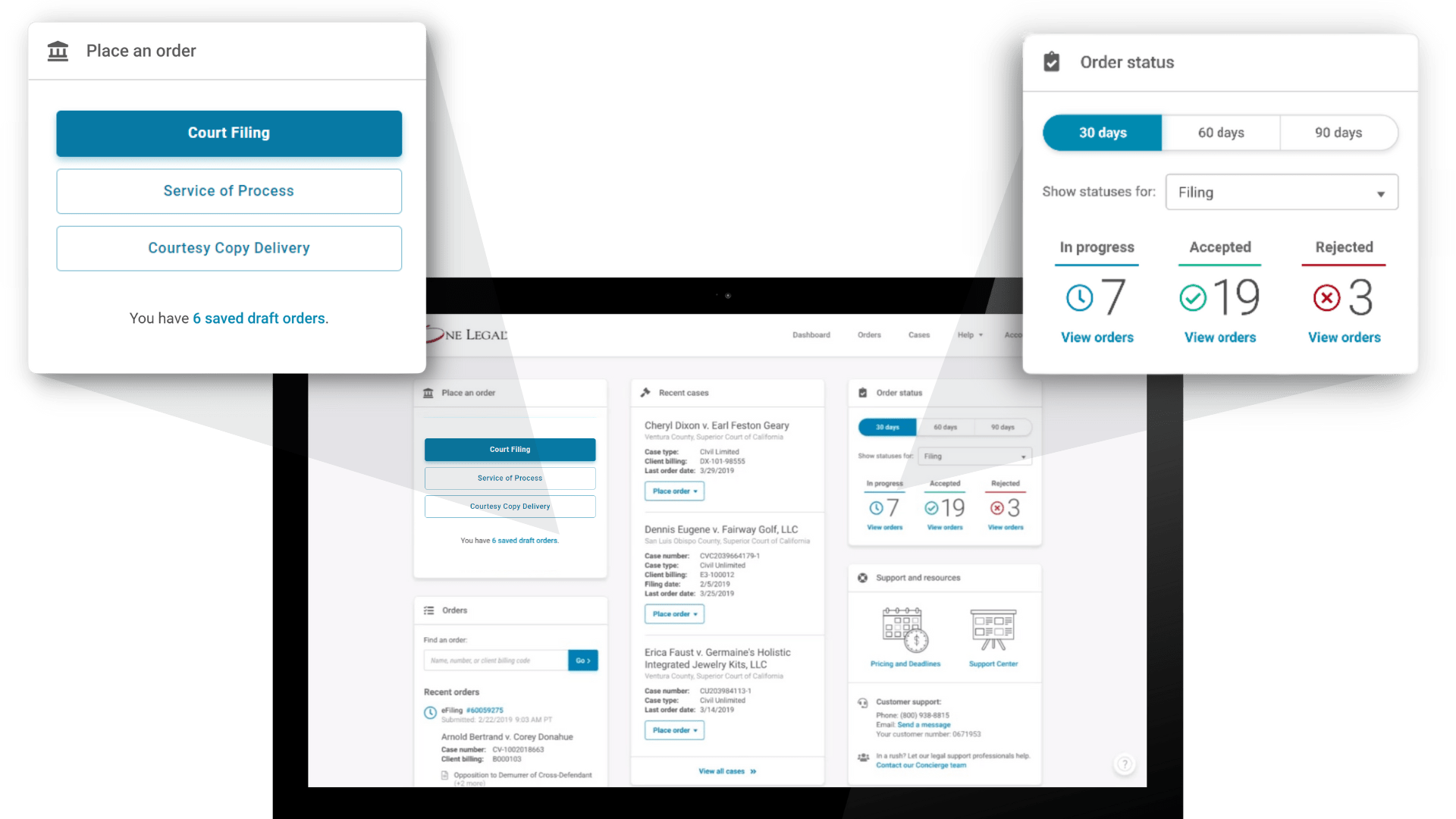

Courts themselves are adopting a number of digital and virtual techniques designed to save time and courthouse space.

For example, electronic filing (eFiling) systems allow legal documents to be submitted online. This streamlines the filing process, reduces the need for physical paperwork, and makes it easier for litigants to manage their cases remotely.

Many courts have embraced online dispute resolution platforms, making the process more efficient and accessible.

Electronic notarization (e-notarization) has been implemented to allow documents to be notarized online, further reducing the need for physical interactions and expediting legal processes.

Courts are increasingly collecting and analyzing data to guide decisions on the use and performance of technological tools. This data-driven approach helps refine and improve court processes to serve litigants’ needs better.

Most importantly, more and more courtrooms are equipped with screens and other electronic devices for trial and hearing presentations.

This equipment eliminates the need for space to store paper exhibits and demonstrative aids. Indeed, some judges even mandate the use of digital materials over paper.

Matheny notes more and more courtrooms are equipped with audio, video and computer monitors, USB, Ethernet and power supply for all counsel. Says Barcus, “The larger courtrooms are plug and play with screens for witnesses to point and draw on exhibits.”

These techniques enable and enhance the use of virtual and remote proceedings for courts and court administrators.

Challenges and the future

Despite all the technological advancements, some challenges need to be addressed.

Ensuring that technology is accessible to all users, including those without high-speed internet or computers, remains a significant hurdle in many locations

But despite this, significant progress has been made in making our courts more of a service and less of a place.

Technology has reduced cost and expense and made court proceedings more convenient for all. While we may not yet be at a place where fully virtual trials are commonplace, we have the technology and tools to at least make it a valid option in some instances.

Barcus sums it up best: “It is amazing what has happened in just the last five years.”